Even novice gardeners are aware of worms as a driving force in the garden, and this is especially so for those no-till beds so popular in permaculture plots. For most of us, it’s no great revelation that soil thick with worms is also likely to be thick with plant growth.

The reasons are many, but in the most basic terms, earthworms are great for aerating soils and transforming organic material into fertile, microbially rich (and hygienically safe) castings.

A Simple Indoor Vermicompost Project

I’ll go ahead and assume that today’s readers are do-it-yourself types, so I will breeze through mentioning that prefabricated worm bins are available for purchase (starting at about $100) and assume yours will be built at home. In this case, there are a few things to consider in constructing one: worms like it dark and cool, the juices will need to drain, they make composting much quicker (eating about half their body weight each day), composting worms are not just any old earthworms, they require rich surface matter on which to feed, and they multiply—figuratively—like rabbits.

• Note: As the worms multiply, it’s possible to halve the bunch (clew or clat) of worms to produce another worm bin or introduce them into the worm bucket in the garden (We’ll get there in a second). But, the worm population will multiply quickly.

Another worthwhile improvement would be to compartmentalize the container. A partition with a few holes drilled in it will essentially make two vermicomposting boxes out of one. This is advantageous because, once one side is full, you can begin filling the other half. Through the holes we’ve drilled, the worms will then migrate towards the food, making it much easier to remove the pure worm castings without having to contend with pulling out handfuls of worms and unprocessed veggie scraps.

This method is perfect for urban and rural settings alike, and it’ll function just fine under a kitchen sink, where the compost bin would likely have been anyway.

A Vermiculture Garden Project

While kitchen vermicomposting systems are great, some would say that having the whole set up outside, in the garden, is probably a more efficient choice. This way the worms can have freedom of movement, hopefully helping with the tilling while they do their real work: quickly converting organic matter into compost. Just as with composting directly in the garden, which feeds the plants when fertile liquids leach into the soil, a vermiculture garden bed, i.e. with a worm bucket, provides steady, effortless, natural fertilization.

Worm-Tower-with-Geoff-Lawton from Permaculture Research Institute on Vimeo.

These work great because they are such an easy and efficient way of handling garden debris, including weeds and especially overripe fruit and veg. Eventually, each bed can have its own vermiculture system to handle the waste while producing super enhanced plant food.

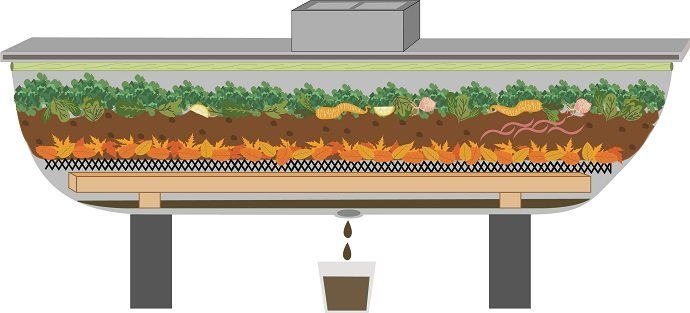

Another popular and contained outdoor system is using recycled bathtubs as large vermicomposting bins, taking advantage of the already existing drain to handle the juices. In this instance, the tub bottom should be filled with a layer of gravel (or timber frame), topped with a wire screen then cover over with—in ascending order—dry bedding, manure and kitchen scraps. And, once again, the whole thing needs a lid.

A Pastoral Vermiculture Revolution

Lastly, there is the more revolutionary act of spreading worms throughout an entire expanse of land, anything from a kitchen garden to a broad-acre pasture. I first learned of this via Bill Mollison’s Global Gardener series from the early 90s. In the “Cool Climates” episode (start at about 17:40), he visits an old friend in Tasmania who has been farming worms — Alibophorus Calliginosa — on a large scale for years.

In other words, once those smaller worm farms are really producing, there is a very productive way of putting the expanded worm population—numbers should grow exponentially within a couple of months—to good use. With the worms then incorporated into our permaculture systems, handling the business of feeding and breeding themselves, the fertility and goodness naturally multiplies. Soils build up, are aerated, become richer in minerals, increase in beneficial microbial bacteria, and are ripe for low-maintenance cultivation.

Source article:

June 28, 2016 by Jonathon Engels & filed under Soil, Soil Biology, Structure, Soil Composition, Design